A crash course in reproducible research in Python

A few weeks ago, I was lucky enough to present at PyCon Australia, right here in my home town of Melbourne. My talk was on reproducible research, an increasingly important concept in science and data analysis as projects become more complicated and datasets become larger (see this recent article, for example, on how a surprisingly high number of genetics papers contain errors because of the way Excel interprets gene names).

I must confess that reproducibility was not a big consideration for me for most of my academic career. To be honest, when I first started doing statistical programming the basics felt so overwhelming that the idea of making it reproducible seemed beyond what I could manage! I also felt a bit overwhelmed by all of the things I seemed to need to learn once I started trying to conduct reproducible research. There just seemed to be so much detail on the web about Git, Github, Jupyter, etc. that I didn’t really know where to start.

Over time, I’ve realised the basics are actually very simple and only require a pretty introductory understanding of the tools you’ll be using. In this post, I’ve tried to demystify both the process and the implementation of reproducible research, and also show you how much easier it makes your life when collaborating on projects or even coming back to your own analyses months later!

What makes an analysis reproducible?

I found a nice little quote on CRAN that defines the purpose of reproducible research like so:

The goal of reproducible research is to tie specific instructions to data analysis and experimental data so that scholarship can be recreated, better understood and verified.

This is a great high-level overview of reproducibility, but its hard to understand how it relates to our day-to-day work. Instead, it might be useful to start with an example of an irreproducible analysis.

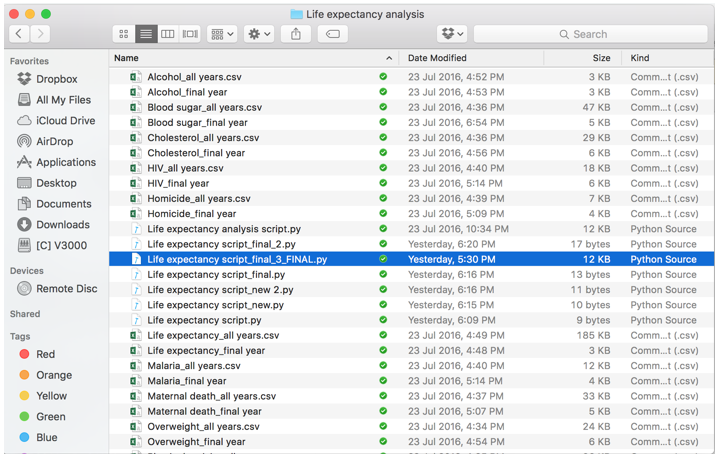

An irreproducible analysis, in my mind, is any analysis that you or someone else has significant difficulties picking up and continuing work to on. Let’s imagine I have an analysis I did 6 months ago, where I used WHO data to predict the average life expectancy in around 150 countries. I open up the Dropbox folder with all of my files:

And I have no idea where to start. Not only are there multiple versions of the analysis script (with no clear pointer to what is the final file), there are also over 30 different datasets. When I open up what looks to be the most recent version of the analysis script (as seen here), there is no real direction as to what the final analysis and findings were, which makes it really difficult to pick up where I left off.

In order to convert this analysis into something reproducible, we need to be able to answer 5 questions:

1. What did I do?

2. Why did I do it?

3. How did I set up everything at the time of the analysis?

4. When did I make changes, and what were they?

5. Who needs to access it, and how can I get it to them?

What did I do?

One of the biggest tripping points when you come back to an analysis is remembering everything you did, and this is made much worse if you have any point-and-click steps.

A common task you might find yourself normally doing manually is downloading your data. However, its really easy to lose track of where you get data from, and which file you actually used. Instead, Pandas has a number of great functions that allow you to download data directly from the web. Below, I’ve used the read_csv function to download a dataset directly from the WHO website. Note that I’ve also included the date that I downloaded the dataset, as well as the website from which I sourced it in the comments.

from pandas import Series, DataFrame

import pandas as pd

# Import life expectancy and predictor data from World Health Organisation Global

# Health Observatory data repo (http://www.who.int/gho/en/)

# Downloaded on 10th September, 2016

def dataImport(dataurl):

url = dataurl

return pd.read_csv(url)

# 1. Life expectancy (from: http://apps.who.int/gho/data/node.main.688?lang=en)

life = dataImport("http://apps.who.int/gho/athena/data/xmart.csv?target=GHO/WHOSIS_000001,WHOSIS_000015&profile=crosstable&filter=COUNTRY:*&x-sideaxis=COUNTRY;YEAR&x-topaxis=GHO;SEX")

Another task that might be tempting to do by hand is editing your data. We’ve all been in those situations where we think, “I’ll only need to do this once, it will be much faster to do this manually!” Unfortunately, it never ends up being just once, and its also really hard to remember what you did later.

It is relatively simple to do all of your data cleaning and manipulation in Python. Those of you who have worked with data before will know how wonderful Pandas is for data manipulation, and it’s pretty straightforward to couple Pandas functions with basic Python to do all of your standard data cleaning tasks. Below I’ve built a function that keeps a subset of columns, keeps a subset of rows, and also cleans up string columns with extra characters and converts them into numerics.

# Create function for cleaning each imported DataFrame

def cleaningData(data, rowsToKeep, outcome, colsToDrop = [], varNames = [], colsToConvert = [], year = None):

d = data.ix[rowsToKeep : ]

if colsToDrop:

d = d.drop(d.columns[colsToDrop], axis = 1)

d.columns = varNames

if (d[outcome].dtype == 'O'):

if (d[outcome].str.contains("\[").any()):

d[outcome] = d[outcome].apply(lambda x: x.split(' [')[0])

d[outcome] = d[outcome].str.replace(' ', '')

d[colsToConvert] = d[colsToConvert].apply(lambda x: pd.to_numeric(x, errors ='coerce'))

if 'Year' in list(d.columns.values):

d = d.loc[d['Year'] == year]

del d['Year']

return d

(As an aside, if you find that you’re struggling with the documentation for Pandas you might find Wes McKinney’s Python for Data Analysis useful. It’s written by the author of the Pandas package, and is my go to guide whenever I get stuck trying to implement something.)

The final step for making sure you know what you did is the very boring, but necessary step of cleaning house after you’ve finalised your analysis. Make sure you make a tidy script when you’re done that contains only those analyses needed to produce your final report or paper or whatever you’re producing the analysis for.

Why did I do it?

So we’ve documented everything we did, but we haven’t really kept track of why we did any of it. This is a bit of a problem, because we make a heap of decisions and assumptions during data analysis that we won’t remember later without writing them down. One way of documenting our decisions during our analysis is writing comments in our script (as per this version of the life expectancy analysis). However, this is really hard to read, and therefore limits how useful its going to be later.

Literate programming is an approach that is designed to get around this limitation of comments, as illustrated by this quote:

A literate program is an explanation of the program logic in a natural language, such as English, interspersed with snippets of macros and traditional source code.

What this translates into is lovely, easy to read sections of text that sit along their corresponding chunks of code. In Python, a really nice way to implement literate (statistical) programming is using Jupyter notebooks. These are browser-based documents that allow you to interactively run code as well as input text, images, tables and dynamic visualisations. The text sections are written in Markdown, which means you can use nice formatting features like headings, bullet points and simple tables. Here is an example of the life expectancy analysis done in a Jupyter notebook, to give an example of how much clearer it makes documentation.

How do I make a Jupyter notebook?

It is super simple to make a Jupyter notebook. To start, open up your terminal and navigate to your analysis directory. If you haven’t already, make sure you now install the Jupyter package:

!pip install jupyter

Now we can launch Jupyter, which will open in your default browser:

!jupyter notebook

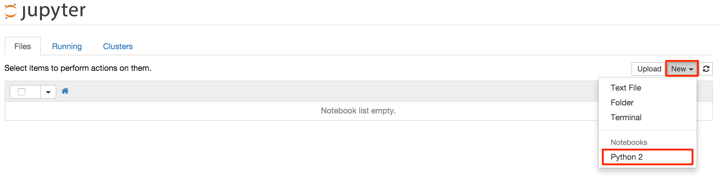

To start a new notebook, simply click on ‘New’ and select ‘Python 2’ under ‘Notebooks’ in the resultant dropdown menu, as below:

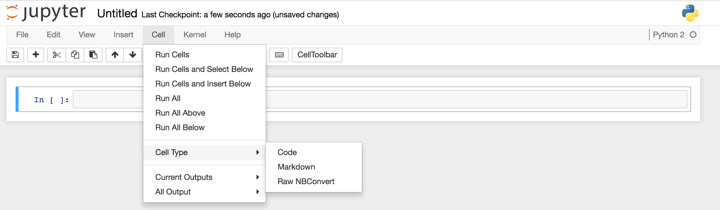

When you are in your notebook, you will have a choice of three types of cells: code (in this case, Python 2), markdown, and raw NBConvert. I rely heavily in my notebooks on switching between code and markdown cells (however, I’ve never explored the NBConvert cells, so feel free to play with those yourself!). To change between these cell types, go to ‘Cell’, then ‘Cell Type’, and change to your desired cell type.

Once you’ve finished typing in the contents of a cell, you can execute it using Shift-Return. And that’s pretty much it! It really is a very simple tool to use for literate programming.

To get out of Jupyter when you are finished, close the browser window and enter control-c at the command line.

How did I set it up?

In the sections above I demonstrated how you can understand your analysis when you come back to it later. However, getting your current machine to be able to excute your script is another thing altogether!

Coming back to our life expectancy analysis, let’s say that when we first completed this project we system-installed the most up-to-date versions of Numpy, Pandas, and Matplotlib. Over the subsequent 6 months, we continually updated to new versions of these package in our global environment. This means we now have a situation where our analysis relies on different package versions to what we have currently installed, which means our scripts may produce different results or fail when we now try to run them.

Luckily, as always, Python has an easy and elegant solution called virtualenvs. The way to think of virtualenvs is that they are essentially just like your global environment, but instead of there being only one environment that affects all Python code run on your machine, you have many different, self-contained and disposable environments that are isolated from both each other and the global environment. You can see how useful virtualenvs are when you have multiple projects all needing different versions of the same packages, as changing versions of packages in the global environment is difficult.

I’ve explained virtualenvs in more detail, as well as how to use and install them, in this blog post. They are super simple to get started with and use - I promise!

When did I make changes?

One of the more difficult things when completing an analysis is keeping track of what changes you’ve made. I’ve already told you that the best way of understanding what you did when you finish your analysis is leaving a tidy script, but what about all of the things you tried that didn’t work and that you want to keep track of? Or the nice bits of code that you don’t need for this project, but that would be useful later?

One really messy and inefficient way (that I admit I am still guilty of at times!) is having multiple files with different versions of the analysis (as you saw at the start of this post). The problem with this approach is that you’ve got no real way of keeping track of what bits of code in the previous versions are actually useful once you’re done, and let’s be honest - you’re probably never going to look through most of those files again.

A way to manage these changes more efficiently is something called version control. This means we use a system to keep track of changes and revisions to our work, while maintaining the current version as our working script. The one I use is Git, which is one of the most popular, but this is by no means the only option!

The way Git works (in my non-technical understanding) is that it allows you to commit a series of snapshots of your work to a special type of folder called a local repository, or repo. This means you can keep track of changes you’ve made to your work (including stuff you’ve deleted) and even go back if you’ve stuffed something up (more detail here). You can see an example of this here, where I’ve added some Markdown text to the beginning of the life expectancy analysis. Git has kept track of what lines I’ve added and deleted, making it easy to compare what changes have been made between the versions.

The other nice thing about version control is that you commit your changes with (hopefully) meaningful messages, which means that you have a record of your thinking about the project as you did it. Here are the commits I did for the life expectancy analysis, to give you an idea - although you ideally should commit more frequently with more descriptive messages than I did!

This gives a nice segue to the next section, on how to share your analysis with others.

Who needs to access it?

When I use Git, I don’t just commit my work to my local drive (I definitely don’t want to lose all of my work if my hard drive fails!). Instead, I commit to a remote repo, which is basically works the same way in terms of taking snapshots of your work but instead saves them remotely.

The website that I use to host my remote repos is called Github. Now the main function of Github is not really giving you a nice, cloud-based backup for your work, but instead is designed to help you share your projects and allow others to collaborate on them. A nice overview (involving cats!) of Github is here, but in summary it allows multiple people to work on a code-based project, and keeps track of who committed what. This means that instead of trying to manually integrate your collaborators’ contributions, they are automatically merged into your project and the changes are kept track of. Most importantly, who made those changes is marked, meaning that if you don’t understand something that a collaborator did you can work out who added the change to the project.

How to do basic version control with Git and Github

The first things you need to do are:

1. Check you have Git installed on your machine (here is a guide for Mac, and another for Windows),

2. Sign up for a Github account, if you don’t have one, and then

3. Set up Github authentication on your machine.

Once you are set up with both Git and Github, the first thing to do is create a remote repo for a new project (see here for an excellent guide on how to do so). You then need to clone a local copy of this repo to your machine, like so.

Once we have our local repo, we can start working on our new Python project. Let’s say we create a new Jupyter notebook (or any kind of code file!), and start work on it. At any point (the more frequently the better), we can make a commit. In order to do so, open the terminal and navigate to the local repo for this project. We then check which files Git is keeping track of (or not) by typing:

!git status

On branch master

Your branch is ahead of 'origin/master' by 2 commits.

(use "git push" to publish your local commits)

Changes not staged for commit:

(use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)

(use "git checkout -- <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

[31mmodified: 2015-11-11-understanding-object-orientated-programming-in-python.ipynb[m

[31mmodified: 2016-06-01-web-scraping-in-python.ipynb[m

[31mmodified: 2016-10-04-reproducible-research-in-python.ipynb[m

Untracked files:

(use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

[31m.DS_Store[m

[31m.ipynb_checkpoints/[m

[31mUntitled.ipynb[m

no changes added to commit (use "git add" and/or "git commit -a")

This is letting us know we have a number of files we’re already asking Git to track that have some uncommitted changes (the ‘Changes not staged for commit’) as well as one that we’re not asking Git to keep track of (the ‘Untracked files’). Files that Git is tracking are ones that have already been committed and which Git checks to see whether any changes have been made since the last commit.

Let’s commit our latest changes to the file ‘2016-10-04-reproducible-research-in-python.ipynb’.

!git add '2016-10-04-reproducible-research-in-python.ipynb'

Git has now popped this file in a queue to be committed, but needs us to explicitly commit the file with a message.

!git commit -m "Completed the final section of the blog post"

[master 8f544a0] Completed the final section of the blog post

1 file changed, 5 insertions(+), 6 deletions(-)

What this command means is that we have committed our changes to the local repo. What we now need to do is push our changes to the remote repo. Pretty much every time I push to the remote, I am pushing to the origin repo on the master branch, which means I use the command below:

!git push origin master

Counting objects: 8, done.

Delta compression using up to 8 threads.

Compressing objects: 100% (8/8), done.

Writing objects: 100% (8/8), 9.43 KiB | 0 bytes/s, done.

Total 8 (delta 4), reused 0 (delta 0)

remote: Resolving deltas: 100% (4/4), completed with 1 local objects.[K

To https://github.com/t-redactyl/Blog-posts.git

83df6d4..8f544a0 master -> master

However, if you have a more complicated repo structure that contains branches, you will need to tailor your push message to make sure you commit to the right place (see this blog post for more details).

That sums up my introductory guide on how to implement reproducible research in Python - I hope you can see with some simple modifications to you (and your collaborators’) workflows, you can have confidence you are building on your previous work and be happily revisiting old projects for years to come!