Types of functions: injective, surjective and bijective

You’re probably familiar with what a function is: it’s a formula or rule that describes a relationship between one number and another. For example, the function \(f(x) = |x| + 1\) describes the relationship between a number and its absolute value plus 1. If you think back to our previous blog post, you can see that what we’re actually describing is a relation, where \(x\mathrel{R}f(x)\) is given by \(f(x) = |x| + 1\).

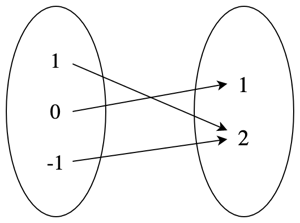

If we take three elements of \(x\), \(\{-1, 0, 1\}\), and pass them through \(f(x)\), we get the set of ordered pairs \(f =\{(-1, 2), (0, 1), (1, 2)\}\). However, we can also imagine this relationship in the form below, where we take the set created by our input elements and map them to the set given by our output elements.

The above example illustrates a few important things about functions that distinguish them from relations. Firstly, as you probably already realised, a function is designed to map the elements from one set \(A\) onto another \(B\), which is denoted as \(f: A \rightarrow B\). In the case of our example above, we were just mapping from a set of three numbers \(\{-1, 0, 1\}\) to another set of three numbers \(\{2, 1, 2\}\).

However, functions can be (and usually are) used to describe the relationship between infinite sets such as the natural or real numbers. In fact, we can keep going with our example function to think about such a mapping. As our input set includes both -1 and 0, let’s imagine that our input set is the integers \(\mathbb{Z}\). What would then be the set be that we’re mapping to? As any \(f(x)\) can never be smaller than 1, then the output set would be all of the natural numbers \(\mathbb{N}\). As such, our function \(f(x) = |x| + 1\) would be defined as \(f: \mathbb{Z} \rightarrow \mathbb{N}\).

This leads to two further observation about functions. While the input and output sets can be the same, they don’t have to be, as in the case of our example. This example also shows that the input set influences what the output set will contain. In our example, the input set contained only integers, so the output set can only contain positive integers. However, if our input set had been the real numbers, then our output set would have been the set of positive real numbers above 1.

The final thing to note about functions concerns how the input elements relate to the output elements. Unlike in relations, every input value \(x\) can only map to one value in the output value \(f(x)\). This means that, for example, a relation that included \((1, 2)\) and \((1, 3)\) would be a valid relation, but would not be a function.

Domain, codomain and range

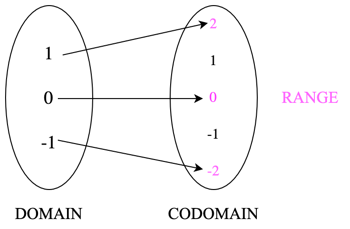

Let’s start giving some names to these parts of functions. Our input set is called the domain of a function, and the output set is called the codomain. Finally, all of the elements in the codomain that are given by \(f(x)\) for every \(x\) in the domain are called the range of the function. Depending on the function, the codomain and the range might be equal, or the range might be a subset of the codomain. This can be see in the example below, for \(g(x) = 2x\), if we imagine that both the domain and codomain are the set of integers.

You can see that the domain maps to only some of the elements in the codomain, those for which \(g(x)\) is twice the elements in the domain. In this case, the range (shown in pink) would be all of the even integers, a subset of \(\mathbb{Z}\).

Types of functions

You’ve probably already noticed when looking at the two functions we’ve talked about so far, that there are different patterns in how the elements in the domain relate to elements in the codomain. In the case of \(f(x) = |x|+ 1\), all of the elements in the codomain map to a value in the domain, but there is not a unique one-to-one relation between them. For example, \(f(-1) = f(1) = 2\). In contrast, in the case of \(g(x) = 2x\), there is not a value in the domain for every value in the codomain. For example, there is no \(a\) in the domain for which \(g(a) = 1\).

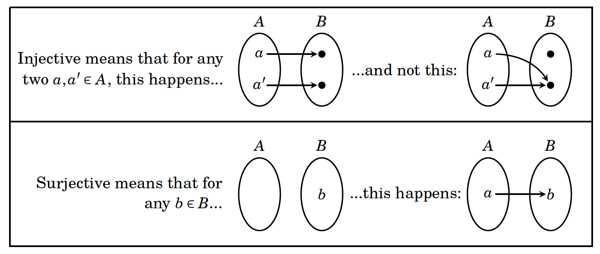

These ways in which the elements in the domain and codomain relate to each other have specific names. When every value \(a, a'\) in the domain \(A\) maps to a different \(f(a), f(a')\) in the codomain \(B\), then we say that this function is injective. From our two examples, \(g(x) = 2x\) is injective, as every value in the domain maps to a different value in the codomain, but \(f(x) = |x| + 1\) is not injective, as different elements in the domain can map to the same value in the codomain.

Conversely, when every value \(b\) in the codomain \(B\) maps to a value \(a\) in the domain \(A\), then we say that this function is surjective. Looking at our examples again, we can see that \(g(x) = 2x\) is not surjective, as all of the odd integers in the codomain do not map to any value in the domain. However, \(f(x) = |x| + 1\) is surjective for \(f: \mathbb{Z} \rightarrow \mathbb{N}\), as every natural number in the codomain maps to an integer in the domain. This raises an important point: whether a function is surjective depends on how the codomain is defined. If we defined the domain and codomain of \(f(x) = |x| + 1\) as \(f: \mathbb{Z} \rightarrow \mathbb{Z}\) then it would not be surjective, as any value of the codomain \(\leq 0\) would not map to anything in the domain.

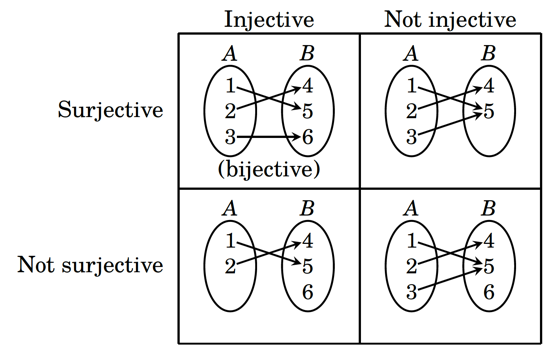

It is also possible for functions to be neither injective nor surjective, or both injective and surjective. This can be seen in the diagram below. In the latter case, this function is called bijective, which means that this function is invertible (that is, we can create a function that reverses the mapping from the domain to the codomain).

Let’s now have a look at how we prove whether a function is injective or surjective.

Proving injection, surjection and bijection

In order to look at how to prove injection and surjection, let’s walk through an example problem.

Prove that the function \(f: \mathbb{R} - {2} \rightarrow \mathbb{R} - {5}\) defined by \(f(x) = \frac{5x + 1}{x - 2}\) is bijective.

We know that if a function is bijective, then it must be both injective and surjective. What we need to do is prove these separately, and having done that, we can then conclude that the function must be bijective.

We’ll start with proving that the function is injective. In order to do this, what we need to do is prove that, for any two elements \(a, a'\) in the domain \(A\), if \(a \neq a'\), then \(f(a) \neq f(a')\). In other words, we need to prove that any two distinct elements in the domain do not map to the same value in the codomain.

The easiest way to do this is usually with contrapositive proof. We start with the assumption that \(a, a' \in A\) and \(f(a) = f(a')\), and we want to show that this implies that \(a = a'\), indicating that the only way in which two elements in the codomain could be equal is if they are mapped to the same element in the domain. Let’s apply this to our problem.

As we know that \(f(x) = \frac{5x + 1}{x - 2}\), then \(f(a) = \frac{5a + 1}{a - 2}\) and \(f(a') = \frac{5a' + 1}{a' - 2}\). We are starting from the assumption that \(f(a) = f(a')\), so substituting in our definitions, we get:

Now we need to simplify this expression to get to \(a = a'\).

We’ve thus shown that if we pick any two arbitrary \(a, a'\) in the domain, the only way their associated \(f(a), f(a')\) in the codomain can be equal is if \(a, a'\) are equal. Therefore our function is injective.

With surjection, we’re trying to show that for any arbitrary \(b\) in our codomain \(B\), there must be an element \(a\) in our domain \(A\) for which \(f(a) = b\). The easiest way to show this is to solve \(f(a) = b\) for \(a\), and check whether the resulting function is a valid element of \(A\). In the case of our problem, we know \(f(a) = \frac{5a + 1}{a -2}\), and we’re trying solve \(f(a) = b\) for \(a\). Substituting in this definition of \(f(a)\), we get:

As long as \(b \neq 5\), then \(a\) is a valid element of \(\mathbb{R}\). As our domain is \(\mathbb{R} - \{5\}\), then this condition is satisfied. Therefore for every \(b \in B\), we have a corresponding \(a \in A\) where \(f(a) = b\). As such, our function is also surjective.

As we have proven that our function is both injective and surjective, we can now say that we’ve proven that it is bijective.

As you can see, although it seems intimidating at first, the principles underlying functions and their proofs are pretty straightforward. Credit for most of the material in this post (including the third and fourth images) goes to Richard Hammack’s wonderful Book of Proof.